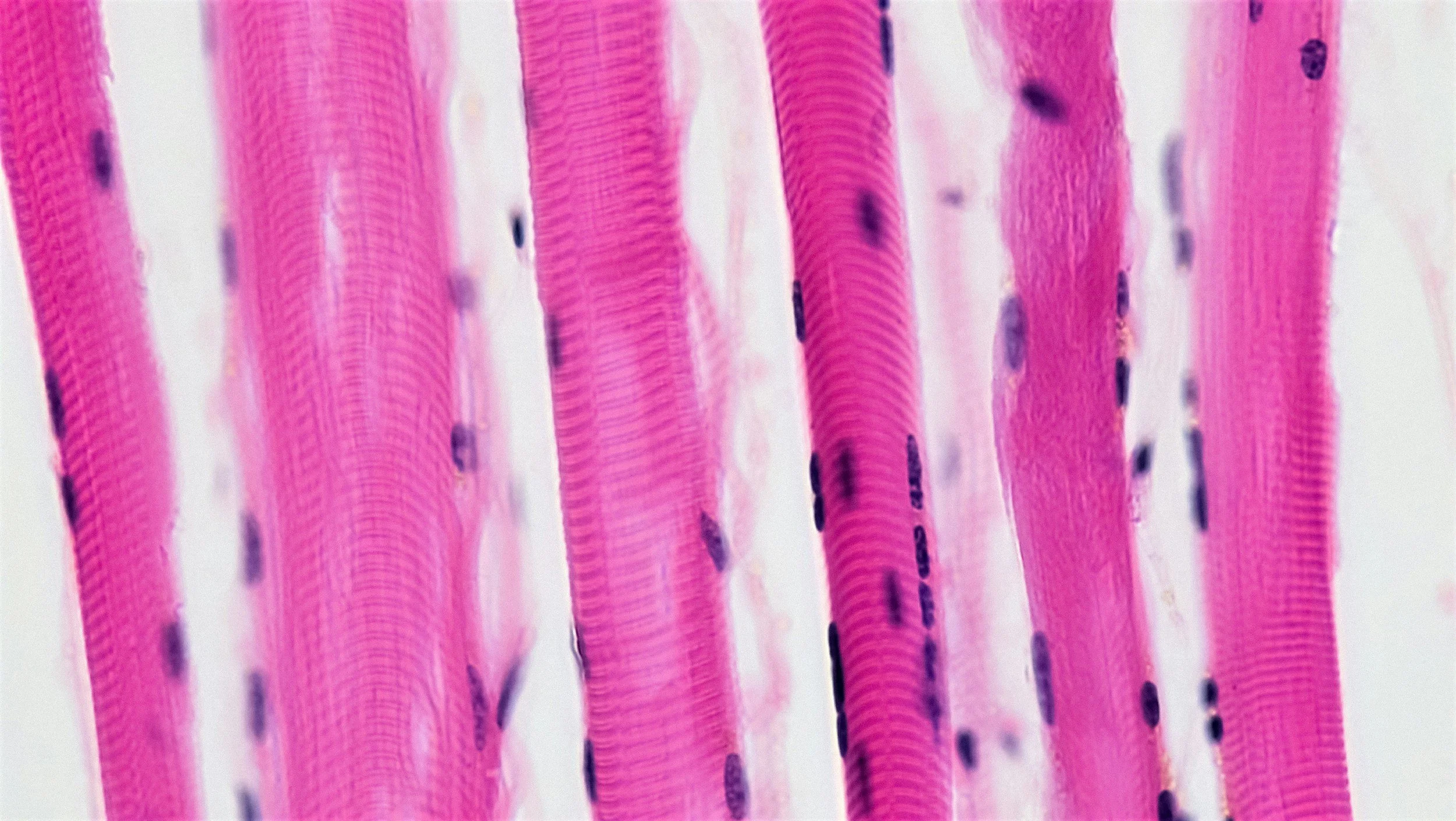

Skeletal Muscle: The Overlooked Immune Organ

The "sick" season is upon us, and it has been a particularly difficult one. In this month's blog, we review a critically important but often overlooked component of immune health: our muscles. When most people think about skeletal muscle, they think about movement, strength, posture, or aesthetics. Rarely do they think of immunity. But modern science and physiology tells a very different story. Skeletal muscle is not just a mechanical tissue—it is one of the largest immune-regulating organs in the human body, exerting meaningful influence over immune surveillance, inflammatory balance, metabolic health, and systemic recovery. There is a continuous dialogue happening between our muscles and immune system, and this conversation plays a major role in directing action against microbial invaders.

Muscle as an endocrine and immune signaling organ

Skeletal muscle makes up about 40% of total body mass. That scale alone should make us suspicious that its role extends beyond just moving bones. When muscle contracts, it releases signaling molecules known as myokines—chemical messengers that communicate with:

Immune cells

The liver

Adipose tissue

The brain

The vascular system

Some key myokine players include:

IL-6 (interleukin-6) – often misunderstood as “pro-inflammatory,” but during muscle contraction it actually plays an anti-inflammatory and immune-regulating role

IL-10 – suppresses excessive immune responses

IL-15 – supports natural killer (NK) cell and T-cell function

BDNF – links muscle activity to brain and immune resilience

It’s important to remember that context matters, and these signaling molecules operate in this positive way only in response to healthy muscle function. Like most things in life, the expression of the chemicals should be on the order of not too much and not too little. The body and our physiology likes it somewhere in between. Through these myokine messengers skeletal muscle functions as a distributed signaling hub, dynamically adjusting immune tone in response to mechanical and metabolic stress.

Muscle as an Immune Buffer

One of skeletal muscle’s most underappreciated roles is its ability to act as a metabolic and inflammatory buffer.

Healthy muscle:

Absorbs glucose efficiently----Quality muscle acts as a metabolic sink, essentially draining the systemic circulation of excess blood sugar and reducing the harmful effects of insulin resistance and diabetes

Stores amino acids needed for immune cell proliferation----Immune cells and antibodies are made up of proteins, and when called to action after infection the immune system needs extra resources to mount it's defense. Quality muscle tissue stores these basic materials and deploys them in coordination with other defense mechanisms.

Helps regulate systemic inflammation----lower baseline inflammation means a better response to signaling and upregulation when necessary.

Improves mitochondrial health (critical for immune energy demands)

During illness or stress, immune cells draw heavily on amino acids—particularly glutamine—stored in muscle tissue. This makes muscles both a fuel reserve and a communication hub during immune activation. When muscle health is compromised, immune regulation often follows.

Practical Implications

If skeletal muscle is an immune organ, then caring for it becomes a form of immune hygiene.

Some principles that emerge:

Regular muscle contraction (65-100% maximum effort) supports immune signaling----Consider 5-15 [hard] sets of resistance training per muscle group per week.

Overreaching or excessive volume can provoke immune flare-ups----Recovery is often overlooked in certain active populations. Breakdown -> Rebuild. Allow 48-72 hours before training a muscle group over again.

Protein adequacy supports both muscle repair and immune cell turnover----Aim for 0.7-1.0 grams of protein per lb of body weight each day. Eat from a variety of sources including plants and animal products. Many Americans under consume protein, make it a point at each meal to get 15-30 grams.

Mitochondrial support (sleep, light exposure, movement variability) matters as much as strength.

It is critically important to remember that more isn't always better. Adequately stimulating muscle with resistance training, allowing time to recover, and fueling with sufficient protein is the most complete and balanced strategy to directly optimize skeletal muscle health, and by direct extension immune system function.

Take care of your muscles, come see Dr. Jeremy at Tribalance Chiropractic!

References:

Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiological Reviews. 2008;88(4):1379–1406.

Pedersen BK. Anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: role in diabetes and cardiovascular disease. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2017;47(8):600–611.

Nielsen AR, Pedersen BK. The biological roles of exercise-induced cytokines: IL-6, IL-8, and IL-15. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 2007;32(5):833–839.

Argilés JM, Busquets S, Stemmler B, López-Soriano FJ. Cachexia and sarcopenia: mechanisms and potential targets for intervention. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2015;22:100–106.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. Sarcopenia. The Lancet. 2019;393(10191):2636–2646.

Lightfoot AP, McArdle A, Jackson MJ, Cooper RG. Inactivity-induced muscle weakness: role of reactive oxygen species and protein degradation. American Journal of Physiology. 2009;296:R337–R345.

Meyer A, Meyer N, Schaeffer M, et al. Post-viral myositis: clinical and biological features. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77(6):567–571.

Hargreaves M, Spriet LL. Skeletal muscle energy metabolism during exercise. Nature Metabolism. 2020;2:817–828.

Missailidis D, Annesley SJ, Allan CY, et al. An isolated complex V inefficiency and dysregulated mitochondrial function in immune cells and muscle in post-viral fatigue syndromes. PNAS. 2020;117(35):21598–21608.

Nieman DC, Wentz LM. The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2019;8(3):201–217.